An

introduction to "Warchild"

The 'Warchild' album was released in 1974

and was the result of a filmproject. The basic theme of

the film would have been: the possible choices to be

faced after death and was in that sense a continuation of

the so heavily criticized 'A Passion Play'. Rees (10, p.

64) states, that the main characters in the abandoned

film "were to have been the not insignificant

personifications of God and The Devil, with the possible

controversial premise that somehow their two roles might

be interchangeable!", or, as Ian Anderson has put

it: "I was trying to say that it's not necessarily

always the case that God is good and the Devil is bad.

God was not averse to turning people into pillars of

salt, whereas the Devil has often given people a good

time, with the odd Pagan festival here and there! I'm not

a Satanist or anything like that, but it seemed like an

interesting concept for a film. The album dealt with

similar ideas, but without the film to back it up it

seemed sensible to wash over the concept and let the

music stand on it's own. The music was initially built

around the film, so the songs had to be constructed in

more orthodox lenghts as opposed to the lengthy Passion

Play structure" (10, p. 64). "The overall theme

of 'Warchild' is that all of us have a very aggressive

instinct which is something we're occasionally able to

use for the betterment of ourselves. At other times,

aggression at its worst is used as a very destructive

element. When it's not at its worst it remains merely

comical. I don't think that aggression is such an evil

thing."(11).

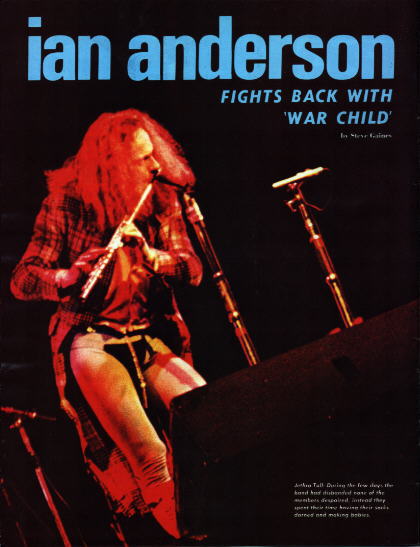

(From: Circus Raves

Magazine, vol. 1# 9, November 1974.

The integral text of this article can be found on Dave Gerber's site. Thanks Dave!)

David Palmer had written orchestral music

for a film of which parts were recorded but got

unfortunately lost in the BBC-studios. Martin Barre wrote

some acoustic material. John Cleese was attracted as

'humor advisor', Sir Frederick Ashton for the

choreography and Bryan Forbes as director. However there

were severe problem getting the financial means together

and when the American film industry was approached for

financial support they made so many severe conditions,

that Ian - partly because the new American tour was about

to start - called the project off. Warchild originally

was meant as a soundtrack album. The album was a return

to the single song format. Two songs were added from the

aborted Château d'Herouville sessions: 'Only Solitaire'

and 'Skating Away On The Thin Ice Of The New Day'.

The album itself was very well sold and

got a reasonable press reaction. The Warchild tour was

very succesfull and continued through most of 1975. A

single was drawn from the album, 'Bungle In The Jungle',

which became to Ian's surprise a big hit in the USA!

A concert poster

from the WarChild tour announcing Jethro Tull's gig at

the Los Angeles Forum. John Glasscock's band Carmen was

the supporting act.

John would join Jethro Tull as a bass player one year

later.

In the introduction to the 'Aqualung' we

described contradictional elements in Ian's music and

stage presentation. Among other things we have seen his

first original compositions as acoustic-oriented music,

and the possibility of his themes deriving meaning from

historical context. We have seen his sardonic humor

combined with serious, sometimes even moralizing

statements (both in plain and in symbolic verselines). At

this point in his artistic development he is both

entertainer and critic - both insightful and tastelessly

vulgar. And he claims that his stage presence is his

physical manifestation of all of this. Is it possible to

link all aspects of his music? Is it possible to place

all aspects of performance and composition into one

framework that will reconcile the contradictions? And can

a framework be found to place the music in a historical

context? I think the answer is found in Ian's

re-invention of the 'minstrel-like' jester, that comes to

the fore in his lyrics, in his music (esp. in the

acoustic, ballad-like songs) and in his stage persona as

well.

The figure of the minstrel as he is

commonly shown is misleading. The languid lute-player in

the Swan Lake suit was not the representative of his

craft in the fourteenth century; rather we should think

of the sly jester of, say, Shakespeare plays, sardonic,

irreverent, plebeian-oriented, outrageously subversive

(Lloyd, 111). The evolution of the image of the minstrel

in the music and in the stage antics of Jethro Tull is

essential to placing the music into the kind of

historical context that will allow insight into its

apparent paradoxes. 'Warchild' was the first album to

consciously make the connection between Tull and the

court jester.

Ian recognized this album as marking the

time when the band "came together" in terms of

sound, and also in terms of the relationship between the

live show and the music (Anderson 7-8). Hardy sums this

up rather succinctly: "In 1974 the group returned to

performing their peculiar brand of rock, theater, and

puerile comedy" (237). But this time around, the

stage show was brighter and happier, and the band members

were dressed in colorful costumes (with Ian's costume

lurking ever closer to the mideval) (Sims 12). Anderson

describes the lyrics to Warchild as suggestive and not

definitive. He also reasserts that his process of

creation is an exploratory process of self-awareness and

self-evaluation. Having recently emerged from the

successes of two U.S. number 1 albums, (the second of

which, Passion Play, received more than its share of

criticism) he was disillusioned about the life of the

rock star. In watching his band spend their newfound

wealth, (most bought houses in the country or cars) he

asserts that he was reminded of "all the things [I]

despise about all the other rock performers" (Sims,

12). The lyrics on this album not only present the

oblique cultural criticisms of the laughing jester, but

there also is the first evidence of the bemoaning of the

lack of a sense of history and place in the modern world.

Annotations

WarChild

WarChild seems to be an anti-war

song. The word WarChild seems to bemoan the fact

that such young men are taken away to die in

battle. The song sarcastically glosses over war

with phrases like "bright city mile",

(lit up by explosions) "all of the pleasure and

none of the pain", "dance

the days and dance the nights away",

(sure, war is all fun & games) and "let

me dance in your teacup and you shall swim in

mine", (as though they still

stop for tea during war -- see also the sound

effect in the beginning: "would you like a cup of

tea, dear?"). The

comical (to me anyway) explosion sound effects

behind the music heighten the sarcasm of the

premise. The final verse seems to say that even

though we mean well defending a country at war,

we overdo it ("open your windows and

I'll walk through your doors")

and then overstay our welcome ("let me live in your

country, let me sleep on your shores").

This may have been a criticism of America's

participation in Vietnam, but I don't know if Ian

was concerned with that at all -- he was more

concerned with England, in general.

* Ian MacFarland

Queen And Country

Ever since 'Thick

As A Brick', we see how in the lyrics of Ian

Anderson more and more historical references,

images and notions are applied. In 'Queen And

Country' he uses the image of sailors who sail

the seas to obtain "gold and

ivory, rings of diamonds, strings of pearls". The verselines "for

Queen and Country" and "it's been this

way for five long years since we signed our souls

away" suggest

that these men signed a Royal Navy contract. I

suspect, that the historical image Ian applies

here is that of the Elizabethan era, when the

Royal Navy, under the command of Sir Walter

Raleigh, raided the coasts of Central and South

America, committing piracy esp. in the Caribbean

and establishing strongholds. These precolonial

expeditions would over time lead to what was

later to be called The British Empire. At first

these actions were aimed at weakening the

hegemony of the Spanish fleet in in this part of

the world and were very lucrative since the

Spanish fleet transported large amounts of gold

and silver that was stolen from Inca's, Aztecs

and other Indian nations to Spain.

The whole song is

written from the sailors' point of view. They

have little to choose since they "signed

their souls away" "for five long

years" at least.

Temptations and amusement have to wait, duty

comes first: "but we all

laugh so politely and we sail on just the

same". In the

words of the sailors the establishment is

criticised: "with the

spoils of battles won" the government and others "can

have their social whirl"and finance their policy: "they

build schools and they build factories". The sailors take all the risks ("hold

our heads up to the gun") during "the long dying

day" (there

is a double entendre here: 'dying' refers to the

nearing end of the day but also to the loss of

men). They face harsh conditions aboard and do

the dirty work that the establishment profits

from and as long as they do so they "remain

their pretty sailor boys".

* Jan Voorbij

I think there might be a bit more

to this song. There seems to be a little parallel

between these sailors and a band on the road.

'It's been this way for five long years, since we

signed our souls away'. When Ian wrote this song

Jethro Tull had been touring for about five

years. 'Schools and factories' were being built

with their tax money, while the band were abroad

for Queen and country. As many other fellow rock

stars they were advised to live in exile and

settle on the continent to avoid the British

taxman. Eventually they missed their Mum's jam

sarnies so dearly that they ran back to Mother

England, even if it meant they had to brake off

their recordings in the 'Chateau d'Isaster'. This

took place shortly before the War Child project,

so I thought there might be a little link here.

What do you think, could it be that the sailors

serve as a metaphor for the band on tour?

* Jeroen Louis

Sealion

One historical template that Ian

invokes in his critique of American culture is

that of carnival. In 'Time Passages', George

Lipsitz explains that there are certain forms

through which popular culture can express a

common memory, attain a sense of history, and

rework their traditions. Carnival is one of those

forms (see Lipsitz 14). The carnival is

characterized by: passions of plenitude, revelry,

free speaking, hearty laughter and most

importantly, the inversion of the social world

and the overturning of convention and propriety

(15). In carnival, there is a valorization of the

street as the place for creativity and society,

and there is a sense of "prestige from

below" (Lipsitz 16). Lipsitz is also

concerned with use of the historical templates in

pop culture as possible tools for the attainment

of hegemony (16). Ian Anderson clearly expresses

his opinion on this in the song 'Sea Lion' from

Warchild. 'Aqualung' and 'Cross-Eyed Mary' have

already made clear Ian's attitudes toward life in

the street: he has portrayed it as brutish and

vulgar.

In 'Sea Lion', Ian calls upon

images of the carnival. "You balance the world

on the tip of your nose, Like a SeaLion with a

ball, at the carnival." and "You

flip and you flop under the Big White Top".

These invoke some impression of the common

characteristics of carnival. There is merriment

and revelry: "You

wear a shiny skin and a funny hat."

But there is a constant reminder of the presence

of authority: "The Almighty

Animal-Trainer lets it go at that."

And of course the carnival can't last forever,

because "you

know, after all, the act is wearing thin, As the

crowd grows uneasy and the boos begin."

There is a possible reference to the reversal of

the social hierarchy and search for hegemony in

the line "So

we'll shoot the moon, and hope to call the

tune." Shooting the moon, in

Hearts, at least, means accumulating all the

losing cards in your hand. Any one of the cards

individually is a loser, but when all of them

come together in one hand their value is reversed

and they become a winning hand. A dangerous

proposition, but with the proper luck and skill,

it's possible to win the biggest by losing the

biggest. So the line could possibly imply a

search for hegemony (in "calling the

tune") by reversing the social order

("shooting the moon"). He comments on

the fragility of the illusion by following with "And

make no pin cushion of this big balloon."

The true message of the song is disdainful and

mocking. He is invoking the image of the carnival

only to ridicule the hopes of

hegemony-through-carnival.

Ian MacFarland comes up with a

totally different explanation and considers the

song as a metaphor for the Soviet Union:

I have been mulling over is

"SeaLion". It seems to me that it

is about a socialist society, most likely the

USSR as it was back then. The first verse is

about the rise of socialism in Russia, and those

who rode the wave. Socialism started with Engels

and Marx in Germany, and for the Europeans who

latched onto their ideas it was only a quick hop "over the

mountains" on their humble "dirty gray horses"

to Russia. But it's all a charade, they're "sad-glad

paymasters", they're having fun

and making money to boot. They live in luxury ("ice-cream castles")

and are in fact masters of capitalism: they make

money ("the super-marketeers

on parade"; supermarkets are the

epitome of capitalism, bigger and cheaper). They

make big deals ("golden

handshake") but it hangs around

their neck like an albatross, marking them as

frauds as they exploit the people for their own

agendas ("light

your cigarettes on the burning deck").

But it's an unstable situation; they may be

lighting their cigarettes, but the deck they're

on is burning. It's so unstable it may as well be

balanced on the tip of the nose. The rulers are

merely SeaLions.

The second verse is about the people. They simply

flop around like morons, being trained to accept

the life you have been given, even though its a

tough life ("whiskers

melting in the noon-day sun").

Notice the leader is a ring mistress, as Russia

is the motherland. But the situation is unstable:

they bark ever-so-slightly

at the trainer'gun, and the act is wearing thin,

as

the crowd is growing uneasy and booing.

The stability may as well be balanced

on the nose. Notice one basic tenet of socialism

holds true: both ruler and subject are merely

SeaLions.

The third verse is about the rulers again.

They're proud of how efficiently they've deceived

the people. Their story is a Passion Play:

they've come in as Messiahs for the people and

"saved" them, but it is, after all, a

play, a show put on for the people. They shoot the moon, win by

losing (as we've seen, in Russia everyone

loses and that's how they're equal; except for

the rulers of course!) and call

the tune, call the shots. But the

situation is only as stable as a balloon pincushion, balanced on

the nose. The rulers are still just

SeaLions.

* Ian MacFarland

(Continuation)

* Judson C.Caswell

(SCC, vol. 4, issue 32, December 1993) ; adaptation and

additional information Jan Voorbij and John Benninghouse;

Works Cited:1. Anderson, Ian. "Trouser Press

Magazine." Autodiscography, (Oct. 1982), 1-13.; 2.

Densflow, Robin. "Rolling Stone." Jethro Tull's

Ian Anderson Plans a Movie; He'll Play God, (11/8/73), 14

; 3. Hardy, Phil and Dave Laing Ed. Encyclopedia of Rock,

New York: Schirmer Books, 1987; 4. Lewis, Grover.

"Rolling Stone." Hopping, Grimacing, Twitching,

Gasping, Lurching, Rolling, Paradiddling, Flinging,

Gnawing and Gibbering with Jethro Tull. (7/22/71), 24-27;

5. Lipsitz, George. Time Passages. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1990 ; 6. Lloyd, A.L. Folk

Song in England. New York: International Publishers, 1967

; 7. Sims, Judith. "Rolling Stone." Tull on

Top: Ian Anderson Speaks His Mind, (3/27/75), 12; 8.

Stewart, Bob. Pagan Imagery in English Folksong. N.J.:

Humanities Press Inc. 1977. 9. Torres, Ben Fong.

"Rolling Stone." Jethro Tull and His Fabulous

Tool, (4/19/69); 10. Rees, David. Minstrels In The

Gallery, A History Of Jethro Tull, Firefly Publ.,

Wembley, 1998, 62-67. 11. Gaines, Steve. "Circus

Rraves Magazine", Nov. 1974.

|

![]()

Back to "Warchild"

lyrics page

![]()

![]()

![]()

Back to "Warchild"

lyrics page

Forward to "Warchild"

annotations page 2

![]()

![]()