An introduction to

"Songs From The Wood"

Jethro Tull would close out the seventies with a

trilogy of albums that would most eloquently and

cohesively express Anderson's world-view. He would

continue with these themes in later albums but these

attempts would prove to be expansions or recapitulations

of the ideas stated in these three works. It is in these

albums that the urban/rural dichotomy comes to the fore

and Celtic/pre-Christian ('pagan') myth and imagery,

which had been used sparingly in the past, is used

prominently.

Previous Tull albums have been generally cynical and

quite trenchant with regards to modern society. With the

album at hand, these elements are inverted. A largely

celebratory mood is invoked with the lyrics in praise of

nature and of past rural life. Previous albums portrayed

modern life as being spirtually hollow and in decay while

the current album portrays a way of life that Anderson

sees as full of meaning with a sense of community and

respect for nature. This environmental theme will be most

prominent in the final album of the trilogy, Stormwatch.

The first track 'Songs From the Wood' begins with the

title track: "Let

me bring you songs from the wood, To make you feel much

better than you could know." These

lines are sung in a madrigal-like acapella chorus. The

narrator wants to show us "how

the garden grows" and to bring us "love from the field."

He urges us to "join the

chorus if you can." He calls us to

become a part of larger community pursuit of a greater

good. Contrast this with the criticisms evident on Thick

As a Brick. It would seem that Anderson is trying to

construct a set of values that would be appropriate for

society to pass onto its young. In an interview the

following year, he would reveal how he has integrated

some of the ideas on the album into his own life: "

... rather than spending his money on drugs, parties and

cars, I would rather have something tangible at my

disposal and also something I can feel a little bit

responsible for. That's one thing money buys: the right

to acquire responsibility for things or people or animals

or whatever".

'Songs From The Wood' is ripe with folk

instrumentation, but it is not folk music. There is

electric guitar and rock drums but it is not rock music.

It is a complex mixture of both these musics and more.

Regarding the appropriation of English folk music

Anderson has said, "It's more than a liking for the

instrument. It's a response to the music - that droning

quality - Celtic music. It's something special. One can't

really pin down what. It has to be some kind of folk

memory." It is also noteworthy that this musical

break with their past involved the inclusion of

'additional material' by David Palmer and Martin Barre.

This album was more of a group effort than past albums.

"Songs from the wood : the music

and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John Benninghouse;

adaptation Jan Voorbij.

As said before, on the albums 'Songs From the Wood','

Heavy Horses' and 'Stormwatch', Ian Anderson makes use of

all kinds of references and images from English folk

song, as Caswell states in his astute 1993 paper:

"In fact the images are too numerous to be dealt

with thoroughly here. However, with just a brief look, we

can find that English folk song is a source of validation

for religious and sexual rebellion. The matter-of-fact

sexual attitude expressed on Songs From the Wood and

Heavy Horses is in no contradiction with true English

folk song. Stuart, in his Pagan Images in English

Folk Song, explains that sex was considered quite

natural and a worthy topic of song (59). Lloyd explains

that in an agricultural society, all kinds of fertility

are sacred--human, animal and plant. He goes on to say,

"Nowhere does this intimate consonance with nature

show clearer than in the erotic folk songs" (197).

Particularly striking images arise from the rite of

Beltane, or May Day: Stories

abound of young men and women running amok in the woods

on the eve before the first of May. Church officials

condemned such practices, swearing that a full two-thirds

of the maidens returned home "defiled" (Lloyd,

106-107). For the pre-Christian peasant, these were not

defiling acts: The first of May was seed time, and after

planting it was believed that the seeds should be

assisted in their fertilization. The sexual energy of the

most virile members of the community was required to

ensure the success of the crops (Lloyd, 106). Young

couples copulated in the furrows of the fields to assist

the crops along as well (99). As a result of these pagan

practices, sexual imagery involving fields and farms is

abundant (200)."

"The sexual imagery on Songs From the Wood and

Heavy Horses is full of such references. The main sexual

songs on the album "Songs From The Wood" are

"Velvet Green" and "Hunting

Girl".(...). All songs involve love in the wide

outdoors."

Jethro Tull during

the Songs From The Wood Tour 1977

Annotations

Velvet

Green

- "is a wonderful pick-up song, sung by a

amorous young man, asking his love to stay with

him and "tell your mother that you

walked all night on Velvet Green."

The song presents sex on the open fields with a

"silver

stream that washes out the wild oat seed",

and though "civilization is raging

afar," the man still urges the woman, ""But

think not of that, my love, I'm tight against the

seam. And I'm growing up to meet you down on

Velvet Green."

- Imagery in this song is reminiscent of images

from an English folk song called "The

Mower," in which the fair maid is

unsatisfied with her beau. "I'll strive

to sharp your scythe, so set it in my hand"

says the maiden (Lloyd, 201). "Velvet

Green" includes the line "Won't

you have my company, yes take it in your hand."

;

Hunting

Girl

- "says: "She took the simple man's

downfall in hand; I raised the flag that she

unfurled." "Hunting

Girl" is another of his sex-in-the-fields

songs. However, this is the story of an

aristocratic lady who seduces a lowly field

worker with wild and extravagant practices:

"Boot leather

flashing and spur-necks the size of my thumb. This

high-born hunter had tastes as strange as they

come.

Unbridled passion: I took the bit in my teeth.

Her standing over: me on my knees underneath."

These playful allusions to sex bear strong

resemblances in tone to many early folk songs,

and Ian's stage gesturing can be related to folk

sources as well. "Bawdiness and

sexuality, loose talk, obscene gestures, priapic

dance, are the starting points for many

ceremonial dramas of springtime"

(Lloyd, 106)." (...)

Jack-In-The-Green

- "This rejuvenation (of nature/life - jv) is

clearer in 'Jack-In-The-Green' from Songs From

the Wood. Jack, as presented in the song, is

responsible for keeping the green alive over the

winter and bringing it out again in spring.

According to Stewart, Jack-In-The-Green is one of

the many names by which Saint George is known. He

is also called the Green Man, is associated with

many fertility rites, including Beltane, and is

responsible for returning leaf and life after

winter. Ian Anderson applies this powerful

healing spirit to a very modern question.

Considering the environmental terrorisms of

industrialization as a kind of winter, he asks:

"Jack

do you never sleep? Does

the green still run deep in your heart?

Or will these changing times, motorways,

powerlines keep us apart?

Well I don't think so, I saw some grass growing

through the pavements today."

This stanza illustrates two things: 1) that there

is hope for modern civilization and 2) this hope

lies in reaching back to tradition for a

different view of the man's relation to nature.

This is a small precursor to the environmental

concerns expressed later in the trilogy.

- "Though the audiences of these songs and

viewers of his shows may not recognize the

specific historical references presented, that

doesn't change the historical significance of the

work (Lipsitz, 104). It is likely that Ian

Anderson doesn't fully understand the images he

refers to: for instance, his Jack-in-the-Green,

according to a concert clip off Bursting Out, is

one of many little woodland sprites that cares

for plants. The explanation is wrong, but the

image serves the proper function nonetheless.

"

- This reflects Lloyd's idea of a folk-memory,

through which connotations remain long after true

meanings are lost (Lloyd, 96). Stewart would say

that the strength of Ian's imagery lies in the

unconscious appeal of the magical symbols, and

that he has tapped into a source of racial

consciousness and identity (Stewart, 13). Lipsitz

says "all cultural expressions speak to both

residual memories of the past and emergent hopes

for the future" (13). Ian's utilization of

old pagan imagery of fertility and rebirth are

being put to work in the present to accomplish a

sense of hopefulness. His agenda at last is not

political, but spiritual, and he accomplishes a

sense of tranquility and rightness for those who

can empathize with his imagery. His goal: "Let me

bring you Songs From the Wood, to make you feel

much better than you could know."

- "Conclusions: Now it is possible to compare

where Ian Anderson is in 1978 to where he started

in 1968, with Roland Kirk. Lipsitz identifies

Kirk as a performer who is deriving his power

from a sense of history. He explains that Roland

Kirk presents an art that can be interpreted at

many levels - an art that makes reference to the

past through oblique and coded messages. These

messages arise as eccentricities in Roland Kirk's

music and stage presence (4). Ian Anderson strove

to make that same kind of historical connection,

and to have that connection be manifest in all of

his works. He felt no sense of group-identity

with the rock 'n roll culture of his times, so he

searched elsewhere for his historical

connections. With these connections he found a

voice for emotional and critical expression. The

imagery of English folk culture permeated his

work and allowed him to evoke the past to

accomplish his artistic goals."

* Judson C.Caswell (SCC, vol.

4, issue 32, December 1993) ; adaptation Jan

Voorbij ;

Works Cited: 1. Anderson, Ian. "Trouser

Press Magazine." Autodiscography, (Oct.

1982), 1-13.; 2. Densflow, Robin. "Rolling

Stone." Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson Plans a

Movie; He'll Play God, (11/8/73), 14 ; 3. Hardy,

Phil and Dave Laing Ed. Encyclopedia of Rock, New

York: Schirmer Books, 1987; 4. Lewis, Grover.

"Rolling Stone." Hopping, Grimacing,

Twitching, Gasping, Lurching, Rolling,

Paradiddling, Flinging, Gnawing and Gibbering

with Jethro Tull. (7/22/71), 24-27; 5. Lipsitz,

George. Time Passages. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1990 ; 6. Lloyd, A.L. Folk Song

in England. New York: International Publishers,

1967 ; 7. Sims, Judith. "Rolling

Stone." Tull on Top: Ian Anderson Speaks His

Mind, (3/27/75), 12; 8. Stewart, Bob. Pagan

Imagery in English Folksong. N.J.: Humanities

Press Inc. 1977. 9. Torres, Ben Fong.

"Rolling Stone." Jethro Tull and His

Fabulous Tool, (4/19/69), 10.

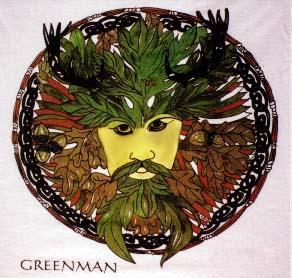

- The Greenman

The powerful foliate head of the Greenman is a

symbol still seen today carved on mysterious

stones, ancient churches and on Celtic artifacts.

In Celtic folklore, he peers at us through the

masks of Cernunnos the Wild stag-horned Lord of

the Hunt, Herne the Hunter, the Green Knight of

Arthurian legend, Jack-in-the-Green (...). He

protects the forest and is the spirit of the land

- and is still used todayas a good luck symbol

for gardeners. His face, carved in golden oak,

can also be seen in Windsor Castle, where it was

restored after their disastrous fire.

* Artwork and

information: courtesy of ę Chris

de Haan

- Neil Thomason has a different opinion on the

origins of Jack-In-The-Green and states: " 'Jack-In-The-Green'

is an English character, as Ian acknowledged

numerous times on stage. Some have argued here

that the song relates to the Green Man. I'd

disagree, but in any case, the Green Man is a

figure of English, not Celtic folklore. Okay,

there's some cross-over, but as generally

understood, he's English."

* Neil Thomason

(SCC vol.9 nr. 14)

- Here are the two references to

Jack-in-the-Green from J.G. Frazer's book 'The

Golden Bough: a study in magic and religion'

(abridged edition, Macmillan 1987): "In

England the best-known example of these leaf-clad

mummers is the Jack- in-the-Green, a

chimney-sweeper who walks encased in a pyramidal

framework of wickerwork, which is covered with

holly and ivy, and surmounted by a crown of

flowers and ribbons. Thus arrayed he dances

on May Day at the head of a troop of

chimney-sweeps, who collect pence [money] . . . .

it is obvious that the leaf-clad person who is

led about is equivalent to the May-tree,

May-bough, or May-doll, which is carried from

house to house by children begging. Both

are representatives of the beneficent spirit of

vegetation, whose visit to the house is

recompensed by a present of money or food."

(p. 129).

And: "In most of the personages who are thus

slain in mimicry it is impossible not to

recognise representatives of the tree-spirit or

spirit of vegetation, as he is supposed to

manifest himself in spring. The bark, leaves, and

flowers in which the actors are dressed, and the

season of the year at which they appear, show

that they belong to the same class as the Grass

King, King of the May, Jack- in-the-Green, and

other representatives of the vernal spirit of

vegetation . . . " (p. 299). All in all,

this book is essential reading for information

about pre-Christian rituals and folk-beliefs.

* Andrew Jackson

- The "Greenman" is in various form

carved into English Christian churches by

stonemasons and woodcarvers, which purport to be

forest-gods from England's pagan past. You can

see some examples of Green Men on these sites:

"The search for the Green Man": http://www.dent.demon.co.uk/index.html

and

"The Green Man: variations on a theme":

http://www.gmtnet.co.uk/indigo/edge/greenmen.htm.

For more specific information, see "Who is

the Green Man": http://emrs.chm.bris.ac.uk/morris/CClarke/GREENMAN.HTM

When I first visited your site I was immediately

struck by the image of Ian Anderson as Green Man

that you use as a repeated motif in your site.

* Harrison Sherwood

Cup

Of Wonder

- This song is a fairly explicit call for the

listener to at least reconsider what tradition

has to offer. The song calls back "those who ancient lines did

lay". A ley line, in Celtic

lore, is a line in the ground along which the

energy of the earth flows. These lines were to

connect sacred sites such as Stonehenge. After

more Celtic images (standing stones, the Green

Man, et al) the listener is asked to: "Question

all as to their ways, and learn the secrets that

they hold." This line

perhaps sums up the message of the entire album

better than any other. Other pagan/pre-Christian

references include the line "Pass the

cup of crimson wonder",

which refers to Druidic human sacrifice. Peg Aloi

interprets the lines "Join in black December's

sadness, Lie in August's welcome corn."

as referring to the pagan holidays of Yule and

Lughnasa.

* "Songs from the wood :

the music and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John

Benninghouse; adaptation Jan Voorbij.

- This has to be among the most brilliant of

Anderson's many brilliant lines: For the May Day is the great

day, sung along the old straight track. And those

who ancient lines did lay will heed the song that

calls them back. (...)"Cup

of Wonder" is about pagan and

quasi-druidical rituals (or how we today imagine

that they were, since nobody knows for sure.)

"Beltane"

is the name of an old pagan ceremony surviving as

May Day (...). Here's why the couplet is so

brilliant: First it contains a literary allusion:

"The Old Straight Track" was a book

published in 1925 by Alfred Watkins, an amateur

archaeologist, about the lines of standing stones

and other megalithic monuments in Britain and

France. He believed that the alignments of the

stones were evidence of, or channels for, some

unknown power in the earth. Deliberately aligning

buildings, furniture, etc. to correspond with

these lines is a type of magic called

geomancy(...). But even more amazing, the next

line contains a TRIPLE pun. There are three ways

of reading "those who ancient lines did

lay": 1) "lay"

means to put or set down; it refers to those who

placed the stones in their alignments. 2)

"ley line" is another term for the

mystical lines of power that are said to be under

the earth. This term was first used by Alfred

Watkins. The origin of the word "ley"

is vague, but may be from "lea" for a

tract of open ground, or the Saxon word for a

cleared glade. 3) "lines did lay" can

also refer to to minstrels writing lays, a form

of poetry (as in "The Lay of the Last

Minstrel," by Tennyson). The term

"lines" then refers to the lines of

words that make up the lay. And we know that Ian

is fond of the idea of minstrels; it makes just

as much sense that the minstrels will "heed the

song" as it does the

original builders of the alignments. The man is a

stone (!) genius.

* Ernest Adams

(SCC vol. 9 nr. 4)

- In the line "pass

the word and pass the lady", lady is probably the

sabbath-cake which many pagans referred to as

"the Lady". Here is referred to witches

sabbat, of which Beltane is one of eight. Cakes

and ale (or wine) is the traditional sacrament.

One would "pass the word" because coven

meetings (where a group of witches would work

magic together) were, after all, secret affairs.

* Jessica

Alexander

Ring

Out, Solstice Bells

- This song is a dance to celebrate winter Solstice

(mostly on the 22nd and sometimes on the 21st of

December) and appeals to rejoice the lengthening

of the days, c.q. the return of the light. In it

dru´ds dance while the narrator calls for people

to gather underneath mistletoe and give praise to

the sun. For many European nations like the

Celts, and the Germanic peoples this festival in

ancient times was one of the major ones of the

year, full of rites and ceremonies of which some

survived the ages like the bonfire/fireworks.

During its spread over Europe, Christianity

claimed this festival by 'implanting' Christmas

as a festival of light on the 25th of December.

The back of the sleeve of the "Solstice

Bells"-EP (released in 1976) has a brief

anecdote describing how the Church co÷pted the

pagan winter solstice celebrating, Yule, and

replaced it with Christmas.

* Jan Voorbij

The

Whistler

- Like 'Velvet Green' this is a love

song. The rural imagery continues. A man,

presumably, offers to buy the object of his

affection mares and apples. He talks of sunsets

in 'mystical places', a line that bring the stone circles

to mind. This image returns in 'Acres Wild'

("I'll make love to you (...) where the

dance of ages is playing still") and in 'Dun

Ringill' ("We'll wait in stone circles, till

the force comes through (...) oh, and I'll take

you quickly by Dun Ringill.").

"Songs from the wood :

the music and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John

Benninghouse; adaptation Jan Voorbij.

Pibroch (Cap In Hand)

- This is a song of unrequited love. A man is

travelling through the woods to his love's home

after hesitating for long to propose to her or

express his feelings. He finds out, that he is

too late for that, since there is another man

with her. Pibrochs (in Gaelic: pi˛baireached)

are a form of funeral music, dirge or lament,

very hard to play and therefore also called 'big

music' (ce˛l mˇr), quite different from the

'little music' (ce˛l beag): jigs, reels and

strathspeys.

* Jan Voorbij

- A pibroch is one of three traditional Scottish

dances. They sound pretty well when being played

by real highlanders; visit any Highland-Game

anywhere in Scotland and you will hear a rich

variety of Pibrochs being played.

* Clemens Bayer

(SCC vol 9, nr. 14)

- A pibroch is a formal Scottish dance, or series

of variations on a theme played by bagpipes.

* Neil Thomasson

(SCC vol.9 nr. 14)

Fire

At Midnight

- Once again a beautiful love song

that describes the joy of coming home from a hard

working day and spending time with one's wife.

Ian said he wrote the song after a long day in

the studio. The song breaths an atmosphere of

relaxation, ease, harmony and - perhaps -

gratitude.

* Jan Voorbij

To summarize: the first album of the 'trilogy' is

mostly celebratory. There are love songs, prurient songs

and songs that celebrate nature and traditions c.q.

folklore from ancient, pre-Christian religions, that were

'nature, earth based'. Modern society makes only the

occasional intrusion into the green world painted by

lyrics and music. 'Songs From The Wood' offers us some special

qualities, and reveals an ingenuity that makes the album

a masterpiece.

* Jan Voorbij

|

![]()

Back to "Songs

From The Wood" lyrics page

![]()

![]()

![]()

Back to "Songs

From The Wood" lyrics page

![]()

![]()